An

architectural history of metaphors(c)

(The

partial history of metaphors in selected periods of architecture)

Barie

Fez-Barringten

1011 La

Paloma Blvd.

North Fort

Myers, Florida-33903

USA

bariefezbarringten@gmail.com

www.bariefez-barringten.com

A version of this monograph was published in:"Architecture:the making of metaphors”: by

Cambridge Scholars Publishing in 2011.My editor is Edward Hart of Glasgow.

and

and

“An architectural history of metaphors”:

©AI & Society:

(Journal of human-centered and machine intelligence) Journal of Knowledge,

Culture and Communication: Pub: Springer; London; AI & Society located in

University of Brighton, UK;

AI & Society. ISSN (Print)

1435-5655 - ISSN (Online) 0951-5666 : Published

by Springer-Verlag;; 6 May 2010 http://www.springerlink.com/content/j2632623064r5ljk/

Paper copy: AIS Vol. 26.1. Feb. 2011; Online ISSN 1435-5655; Print ISSN

0951-5666;

DOI

10.1007/s00146-010-0280-8; : Volume 26, Issue 1 (2011), Page 103

Abstract

This paper presents a review and an

historical perspective on the architectural metaphor. It identifies common

characteristics and peculiarities - as they apply to given historical periods –

and analyses the similarities and divergences. The review provides a vocabulary

which will facilitate an appreciation of existing and new metaphors.

Keywords: metaphor, architecture,

art, traditional or classical art, ancient prehistoric, modern and

contemporary architecture

Introduction:

History

is a metaphor of time, space and realities segmented into subjects and themes.

The history of metaphors in periods of architecture is one such reality.

Thucydides said: “History is philosophy teaching by example” (Strassler, R. B

(1942) and Santayana said: “Those who fail to learn from history are doomed to

repeat it” (Santayana (1988). While so many important people have given their

views on history, it is still a vehicle for communicating metaphors because

each of these metaphors encapsulates and recalls the commonplace and artifacts

of its time.

On the

other hand, to modern art and architecture professionals, history is

purposefully ignored in favor of new, innovative and contemporary expressions.

Furthermore, while beauty is in the eye of the beholder, aesthetics is one of

the commonplaces of metaphor. It is personally and culturally of its time and

place but also has some relevance and utility to future generations. In a

sense, historians are cultural “voyeurs” and they actively seek to compare their

own metaphors with others. Do they do so in the belief they will find a yet

undiscovered metaphor in the past which will give them a clue for the future?

Or do they do it in order to clarify the metaphor of their own time? In either

case, metaphorically, they are “carrying-over” and “transferring” from one time

to another by the very act of making metaphors. As many study the Old Testament

to find its law, so historians study history in search of truths: in this case

metaphors and design. As architecture is the process of making of metaphors,

correspondingly each period in history is marked by its own particular

contributions.

Contemporary

architecture is more about unseen and implicit metaphors, where the metaphor is

between elements and factors of program, building technology and social

context. It is more the essence of the architecture; the making of metaphors

than that overview of the apparent historical evidence of these metaphors.

In his

introduction to Robert Venturi's, Complexity and Contradiction, Vincent

Scully observed that 1966 represented an absolute break with pluralism and

initiated the development of what he termed “cataclysmic planning principles”.

In one lecture he observed that contemporary planners and architects had

embraced the idea of destroying the past for the sake of the future. Whilst

eminent domain and commercial interests often result in benefits for the

public, they often do so at a price which neither the public nor the owners can

sustain. By removing and replacing one structure with another, the encapsulated

referent of the past in one context is lost forever. It is arguable that urban

planning which accommodates free enterprise and a role for quasi-government

landmark commissions is more productive in delivering financial viability and

protecting the public good. Since Scully’s statement, such commissions have

flourished and been successful, in one sense referring to the replacement of

landmarks with new buildings and in another with the hegemony of today’s

principles over those of yesterday.

In

psychology, “appreciation” is a general term for those mental processes whereby

an experience is brought into relation with an already acquired and familiar

conceptual system. The metaphoric works were as sensational as the edifices of

the world’s affairs, as monuments were to society’s triumph over evil, nature

and adversity. However, in each period there are exceptions, such as merchant’s

buildings that stood above mass housing; mass housing never nearly replicated

the public buildings. It isn't until later when mass housing, even in Greece

and Rome, replicated scaled-down versions of Greek and Roman temples and the

applied stucco decoration, rendering and false roofs of city townhouses

emulated classic mansions. Even today’s plethora of global subdivision housing

and New England “salt shaker” houses emulated the metaphors of the classic

(Egyptian, Greek and Roman) ideals.

The commonplace to any

one of most of history’s metaphors is the commonplace of the metaphor of them

all; their collective metaphor; the metaphor they all have in common. That is,

that by knowing one you know the others; that one speaks in terms of the other

and that anyone or the collective make the strange familiar.

That is to say: the

example of their commonplaces is turf (area of influence), identity,

security, status, power, protection, shelter and religious purpose and

use (such as rituals, teaching and networking). These commonplaces transfer

from one to the other period in history and represent the collective

commonplace of the history of all metaphors in different periods of

architecture. In any case, “Metaphors simply impart their commonplaces” (Boyd,

R (1993).

Whether central or

decentralized, publicly perceived architectural metaphors are all about names,

titles, and the access the work provides for the reader to learn and develop.

They also symbolize the trade and value of its owner, users and society. In

free- enterprise democratic societies where central government allows for

sovereign citizens to contract, own land and build, there is a rush for them to

emulate historical models to build identity, security, and status into the

ideals of their metaphors. At its best the vocabulary of the parts and whole of

the metaphoric work (building or work of architecture) is an encyclopedia and

cultural building block. The work incorporates (is imbued with) the current

state of man’s culture and society, which is like an “open book” for the

reader. The freedom of both the creator and reader to dub and show is all part

of the learning experience of the metaphor (Kuhn, T. S (1993). In the

metaphoric period of the ‘60s, I coined the term “Pop Arch” to describe the

phenomenon of “popular architecture”.

| Fontainebleau chateau |

“There is not only a

past; there is also a future. No art- and certainly no architecture- is

produced without some awareness of the future. This takes many guises. There is

first the plan of the work to be accomplished and the function to perform. Is

the object a church, a school, a pavilion, a cage, a roadway, a city?”(Weiss,

P. (1971).

|

| The U.S. Gold Bullion Depository Fort Knox |

| Vauban Fortress |

| Governor's Palace in Williamsburg |

In fact

we can see a relationship between the metaphors of a period in the abstract

quality of an ancient pyramid juxtaposed with contemporary geometric building

designs.

The dimension of the

technical metaphor remarkably subdivides periods but none changed the paradigm

as the indoor and stacked plumbing, structural iron and steel, elevators, electricity

and mechanical heating and air-conditioning.

Ancient

and prehistoric architecture is remembered for its caves and hieroglyphics

while the creation and use of metaphors in architecture can be traced back to

places like Tel Turlu in present-day Syria. Most early human shelters either

took the form of a cave, or as evinced by settlements in the Near East, which

date from 4300BC to 1100BC, the form of mandala-shaped ground excavations. The

word ‘mandala’ means a circle in Sanskrit, the language of ancient India. It

represents wholeness and can be seen as a model for the organizational

structure of life itself- a cosmic diagram. For some the metaphor connects to

earth energies and the wisdom of nature and for others as a device to capture

the images of the countless demons and gods (Gardiner, S. (1974). NOTE: The Romans also had the idea of a Celestial Templum.

These

are metaphors, in that they have two referents which liken themselves to each

other and claim a commonplace. The very fact that mandalas are drawn in the

form of a circle, can lead us to an experience of wholeness when we take time

to make them and then wonder what they mean. In the strict use of the mandala,

there is a central point or focus within the symbol from which radiates a

symmetrical design. This suggests that there is a center within each one of us

to which everything is related, by which everything is ordered, and which is

itself a source of energy and power.

| Mandala |

One can only surmise

from the evidence and findings that, for example, one cave housed a collective

tribe and within there were some who hovered together to secure for themselves

one personal space (turf) (Brown, D. (1991). To be claimed, perhaps this place

in the cave had to be identified, secured and addressed. Continuing the

example, when this same group went and found its own cave, as did so many

others, they may also need to be identified, secured and defended. Each time a

metaphor talks about one thing (the tribe) in terms of another (the sign, the

contour or location of the cave). Roaming away from the cave to the prairies,

rivers and lakes, they dug holes in the ground to copy and “dub” the cave in

the ground, they made metaphors of their cave and the mandalas. Each time

something they can do with their hands (techne’) and their thoughts (concept);

both the primary constituents of metaphor (Gordon, W. J. J. (1971).

The

vertical side of the ground replaced the cave’s walls. They considered new

concepts as being characterized in terms of old ones (plus logical conjunctives)

by the circular mandala form; the metaphor-building clarified their location,

status and value. Virtually every known spiritual and religious system asserts

the reality of such an inner center (Pylyshyn, Z. W, (1993). “The Romans

worshiped it as the genius within. The Greeks called it the inner daemon (a

subordinate deity, as the genius of a place or a person's attendant spirit).

Christian religions speak about the soul and the Christ within. In psychology

they speak of the higher self” (Lakoff, G. (1993).

| Çatalhöyük Hose: Syria |

| The Vitruvian Man Leonardo da Vinci |

It is dramatically

represented by DaVinci's Vitruvian man who is based on the correlations of

ideal human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect

Vitruvius (Lakoff, G. (1993).

| Empire |

The two

referents of the metaphor are the geometrical proportions of the ideal human

figure with scale as the commonplace. As the human figure is to the space so is

the volume (height, width and depth) of the space. A huge volume would dwarf

the figure while a small volume could exaggerate the size of the man. Both

classical and contemporary design takes advantage of scale as a design tool and

itself the apparent metaphor.

In

Ancient Egypt the symbolic pyramids, pottery, and large scale temples gave the

Napoleonic period its “Empire” styles and later still the “Biedermeier”

furniture style. Metaphorically, the pyramids are a mystery as we can see the

referent of the current context; but historians cannot absolutely finalize the

other referent of the metaphor. “The founding and ordering of the city and her

most important buildings (the palace or temple) were often executed by priests

or even the ruler himself and the construction was accompanied by rituals

intended to enter human activity into continued divine benediction”

(Copplestone, T. (1963).

Contrast

this metaphor to contemporary metaphors involving, for examples, Fortune 500

corporate images, a new town or a real estate development, commercial retail

chains (i.e. McDonald's , and public housing or public works projects. The

Egyptian example kept tight control on the overt conceptual metaphor and used

the building as a state instrument.

Often

these are dubbed onto the culture to invest with a name, character, dignity,

title, or style (Kuhn, T. S (1993). Metaphors are often signs and monuments to

spiritual beings in an effort to say ‘as they, so are we’; or “as we, so are

they”. In 21st century democracies, or would-be democracies, such divination

reminds people to distrust metaphors and metaphoric thinking, supposing they

allude to un-popular metaphors of religiosity, anarchy and despotism. Wishing

not to recall the oppression under Turkish occupation, the kingdom of Saudi

Arabia does not maintain the buildings built during that time. In a similar

respect, present-day Germany and Italy are often ambivalent about what to do

with the architectural vestiges of National Socialism and Fascism.

As

noted earlier, contemporary architecture is more about the unseen and implicit

metaphors where the metaphor is between elements and factors of program,

building technology and social context; it is less about the gestalt and more

about its component parts. It is more the essence of architecture; the making

of metaphors than that overview of the apparent historical metaphor. Yet,

today, in synthetic urbanisms, metaphors attract and provide scenarios of

metaphoric lifestyles providing all the mainstay commonplaces. Ancient

architecture was characterized by the tension between the divine and mortal

world, even cities, where metaphor markings contained sacred space over the

outside wilderness of nature. The temple or palace continued this role by

acting as a house for the gods.

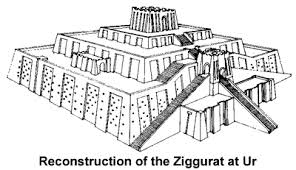

Of

these the most famous was the first city of Babylon (Baghdad) built around 600

B.C. in Lower Mesopotamia in the Neo-Syrian Empire. In it was one of the Seven

Wonders of the World: the hanging gardens of Babylon and the famous Ziggurat

which were the focal and spiritual centers of the city. It was amongst

the first urbanizations where urbanizations occurred between 4000 and 3500 BC

(Sundell, G.

(1988) The City of Baghdad was the first city where its citizens surrendered (primary

definition of Islam) their rights to a “straight easement” to create straight

streets off the walled houses and properties (Hakim, B. (1958). If ever a city

had a metaphoric commonplace it was to be found in the “straight street”.

Perhaps, this is the first sign of a city when its citizens surrender their

rights of space and yield right of ways and easements so that the whole may

function (Akbar, J. A. (1988). The oldest civilization we know is the Sumer -

located in the far south of present-day Iraq. Around 6,000 years ago, the

Sumerians built the world's first city - Uruk – and thus introduced urban

civilization to the world.

its citizens surrendered (primary

definition of Islam) their rights to a “straight easement” to create straight

streets off the walled houses and properties (Hakim, B. (1958). If ever a city

had a metaphoric commonplace it was to be found in the “straight street”.

Perhaps, this is the first sign of a city when its citizens surrender their

rights of space and yield right of ways and easements so that the whole may

function (Akbar, J. A. (1988). The oldest civilization we know is the Sumer -

located in the far south of present-day Iraq. Around 6,000 years ago, the

Sumerians built the world's first city - Uruk – and thus introduced urban

civilization to the world.

(1988) The City of Baghdad was the first city where

It is

at the confluence of the two great rivers, the Tigris and Euphrates at the site

of what was the Fertile Crescent and is now the present-day location of Basra.

It was urban because it had infrastructure which included water,

sewers, roads and law and order. Metaphorically, the city was a reification of

authority and consensus, represented by the widespread use of “seals” which

point to a rudimentary form of government (Schmidt, J. (1964).

|

| Gilgamesh |

| City of Sumer |

It is

thought that the expansion was driven by the necessity for raw materials such

as base metals, timber, common stone and oils; as well as exotic goods such as

rare metals, semi-precious and precious stones, of which none was to be found

in the alluvial plains of the south.

The

necessity of these essential goods led the Uruk culture to establish a number

of urban communities along the lines of older trade routes attained by either

tribute to local rulers, small foraging insurgencies and plundering, or more

commonly by reciprocating with labor intensive processed and semi-processed

goods. It produced the metaphor of pomp, pageantry and ostentatious wealth. As

many later cities built trade crossroads, so the city itself was a metaphor of

those commonalities and differences it accommodated (Jeziorski, M. (1993). More

often than not designers were influenced by the existence of similar types than

to re-invent themselves from scratch. Like a dance they emulated one another.

“The architect, be he priest or king, was not

the sole important figure; he was merely part of a continuing tradition”

(Hitchcock, H-P. (1958). Indeed, these master builders made the kind of

metaphors that communicated overtly and left no doubt as to their intent or

meanings. The Egyptian pyramids were early examples of implicit metaphors where

all the metaphors were not for the public but for the gods. They were meant to

communicate but not to the general public. Most were built as tombs for the

country's pharaohs and their consorts during the Old and Middle Kingdom

periods. As such they were built far away from population centers.

| The largest of the Pyramids at Giza is the "Great Pyramid" |

In

geometry, one form of pyramid is a polyhedron formed by connecting a polygonal

base and a point, called the apex. The pyramid is an elegant metaphor where

each base edge and apex forms a triangle. It is a conic solid with a polygonal

base. The other, a tetrahedron has a three rather than the four side base

(Nuttgens, Patrick (1983). The pyramids are claimed to have many

"secrets;" that they are models of the earth, that they form part of

an enormous star chart, that their shafts are aligned with certain stars, that

they are part of pare of a navigational system to help travelers in the desert

find their way, and on and on. The mystery of the referent is exaggerated

because it is out of our current context and its referent is unknown. The Great

Pyramid is said to contain the metaphor of the “Golden Ratio”. Buckminster

Fuller extended the geometry of the triangle to form the geodesic dome, which

he later explained derives a universal structure seen in the stars (Fuller, R.

B. (1975). The metaphor of the pyramid’s technology depended on nature but was

conditioned by the mechanics of pulleys, cable and the invention of the wheel.

Architectural

metaphors are composed of both conceptual and technical metaphors as {1} art

involves a craft. Little known to historians is that much of the Egyptian

temple architecture (post and lintel) was derived from the “up-river” Sudan.

This exemplifies that although much of our conceptual system is metaphorical; a

significant part of it is non-metaphorical.

“Metaphorical

understanding is grounded in non-metaphorical understanding” (Lakoff, G.

(1993). Our primary experiences grounded in the laws of physics of gravity,

plasticity, liquids, winds, sunlight, etc. all contribute to our metaphorical

understanding where the conceptual commonality accepts the strange.

| Mesoamerican architecture |

Mesoamerican

architecture is mostly noted for its pyramids which are the largest such

structures outside of Ancient Egypt” (Bannister, F. (1996). They are not unlike

the Greek or Roman cities formed on a single spine off which are symmetrically

placed buildings such as temples, markets, baths, halls and ball courts. Over

time and changing periods, like many of the temples in Europe, they were built

over each other and when excavated one can uncover layers of periods of older

temples buried beneath; most notably in Split, in Croatia, where in one

building the layers of time are accessible to the public and can be seen from

outside as well as by climbing down to the lowest level.

A

German ethnologist, Paul Kirchhoff, defined the Mesoamerican zone as a culture

area based on a suite of interrelated cultural similarities brought about by

millennia of inter- and intra-regional interaction (Kirchhoff, P. (1963).These

included sedentarism, agriculture (specifically a reliance on the cultivation

of maize), the use of two different calendars (a 260 day ritual calendar and a

365 day calendar based on the solar year), a base 20 (vigesimal) number system,

pictographic and hieroglyphic writing systems, the practice of various forms of

sacrifice, and a complex of shared ideological concepts; intriguing way that

this Greek for middle became the metaphor for the combined culture and its

unique commonplace (Carrasco, P. (2008).

The

Saudi Arabians use the Hydra calendar, which subdivides 12 months into 30 day

intervals and is annually adjusted by the appearance of the moon. What is most

striking throughout Saudi Arabia is the way city grids are oriented toward

Mecca. And if they were not the qiblah and its minbar of the mosque is

built off the grid of its context to face the Kaaba in Mecca. There are many

other details of Saudi Arabian architecture which provides insights into the

way many of the ancient metaphors were designed.

For

western culture the period of ancient Greece resonates till today. Both the

Greeks and the Roman metaphors were based on their orders of architecture

including their metaphoric columns, entablatures, statues and sculptures

(Bannister, F. (1996). Each of these referred to something else; the column was

the tree and capitals defined one from the other order (Doric, Ionic, and

Corinthian), and the entablatures contained depictions of their deities and

heroes. The architecture and urbanism of the Greeks and Romans were very

different from those of the Egyptians or Persians in that civic life gained

importance. During the time of the ancients, religious matters were the domain

of the ruling order alone; by the time of the Greeks, religious mystery had

skipped the confines of the temple-palace compounds and was the subject of the

people or “polis”. The conceptual metaphor embodied Greek civic life

sustained by new, open spaces called the “agora” which were surrounded

by public buildings, stores and temples.

The “agora” embodied

the new found respect for social justice received through open debate rather

than imperial mandate. “Though divine wisdom still presided over human affairs,

the living rituals of ancient civilizations had become inscribed in space, in

the paths that wound towards the acropolis for example. Each place had

its own nature, set within a world refracted through myth, thus temples were

sited atop mountains all the better to touch the heavens” (Bannister, F.

(1996).

|

| Greek Orders of Architecture |

These

were “analogical transfers”, where instructive metaphors created an analogy

between a to-be-learned- system (target domain) and a familiar systems

(metaphoric domain) (Mayer, R. E, (1993). Later, not unlike classical Gothic,

modern architecture likened to express the truth about the building systems, materials,

open lifestyles, use of light and air and bringing nature into the buildings

environment. Modern architecture went a step further, ridding buildings of the

irrelevant and time worn clichés of building design decoration, and traditional

principles of classical architecture as, for example, professed by the Beaux

Artes movement.

In

modern and Eastern architecture the equipoise achieved by the axiom of “unity,

symmetry and balance” was replaced by “asymmetrical tensional relationships”

between “dominant, subdominant and tertiary” forms, and the influence of

science and engineering on architectural design gave rise to new design

metaphors. The Bauhaus found the metaphor in all the arts, the commonalities in

designing architecture, jewelry, furniture and clothes.

One way

to look at the metaphoric unity of Roman architecture is through a new-found

realization of theory derived from practice and embodied spatially. Civically

this is found happening in the Roman forum (sibling of the Greek agora), where

public participation is increasingly removed from the concrete performance of

rituals and represented in the decor of the architecture. Thus we finally see

the beginnings of the contemporary public square in the Forum Iulium, begun by

Julius Caesar, where the buildings present themselves through their facades as

representations within the space.

As the

Romans chose representations (metaphors) of sanctity over actual sacred spaces

to participate in society, so the communicative nature of space was opened to

human manipulation. None of which would

have been possible without the advances of Roman engineering and construction

or the newly found marble quarries which were the spoils of war; inventions

like the arch and concrete gave a whole new form to Roman architecture, fluidly

enclosing space in taut domes and colonnades, clothing the grounds for imperial

rule and civic order. An unintended consequence was a model for social concerns

and accommodations (public baths, toilets, markets, parks, recreation areas, crafts,

etc.).

The

Romans widely employed, and further developed the arch, vault and dome. Their

innovative use of concrete facilitated the construction of the many public

buildings of often unprecedented size throughout the empire. These include

temples, baths, bridges, aqueducts, harbors, triumphal arches, amphitheaters

circuses, palaces, mausolea and in the late empire, also churches (Bannister,

F. (1996).

Through

the metaphors of law and order, civic pride led to architectural

simplifications of the structure keeping the treasure hidden but exemplifying

the metaphor of the government in its “order” of architecture as metaphor for

the government’s civic order. As the government did, so the architecture exuded

technical and conceptual metaphorical forms of unity, symmetry and balance. As

the Egyptians did, so the Greeks and the Romans built monuments as sign-

metaphors to publicly express consensus toward gods, persons and events.

Temples were built to house the gods such as Venus and Apollo as well as the courts

of justice and senate (Bannister, F. (1996). The architecture metaphors

were the representation residue of the consensus and righteousness of society.

Elsewhere,

“India’s urban civilization is traceable to Mohenjodaro and Harappa, now in

Pakistan. Over a period of time, ancient Indian art of construction blended

with Greek styles and spread to Central Asia. India’s metaphors are their

distinctive design of temples and colorful Hindu art which incorporated

statues, appliqués, pilasters and columns of the many aspects of their deities

including Rama, Saraswati, Hanuman, Ganesha, Devi, and many others

(Copplestone, T. (1963). They were both metaphor of their contextual consensus

while being analogies of their foreign political, social and commercial alliances.

| Chinese Pagodas |

The

ancient Japanese architecture is best exemplified by the metaphoric Japanese

tea house, where bamboo and paper walls remain Japan’s metaphoric cultural

legacy. “Two new forms of architecture were developed in medieval Japan in

response to the militaristic climate of the times: the castle, a defensive

structure built to house a feudal lord and his soldiers in times of trouble;

and the shoin, a reception hall and private study area designed to

reflect the relationships of lord and vassal within a feudal society” (Ching,

F. (2006). Most notably is the Japanese tea house which is “place” but not

“function” oriented. Any function can occur in any area and areas may or may

not be separated by sliding paper partitions. Operations and circulation

metaphor is to the context of the designed landscape which is the architect’s

version of a kind of paradise. Western architecture’s sighting of castles,

estates and private residences learns from this metaphor relating family

occupants to context concerned with topography, surrounds, winds, sun-rise and

sunset and other bio-climatic factors. In the background was origami (the art

of folding paper) which has recently been adapted by mathematicians to design

buildings, sculptures, and furniture made part of the (conditions, operations,

ideals and goals) program. Such systems potentially can result in such

buildings as recently designed for the Emirates (Dubai, Doha, and Abu Dhabi),

Shanghai, and Hong Kong.

Islamic

architecture: Bedouins are nomadic and tent

design and layouts are concerned with the environment of the desert and arrayed

with the tribal metaphors emblems, colors, banners and carpets (Fez-Barringten,

B.(1993). “Each color and combination of colors is distinctive to the family

and “turf” of the tribe. Some distinctive structures in Islamic architecture

are mosques, tombs, palaces and forts, although Islamic architects have, of

course, also applied their distinctive design precepts to domestic

architecture.” Like the retail mall of today the Arabian souks each has

metaphors of their culture, craft and artistic technology. The architecture of

the Arabian souk emulates the Bedouin tents and makeshift gathering of traders.

Arab homes are surrounded by walls and windows clad with mashrabia for

privacy particularly for the family and its women. There is a separate area of

the home for the family and the visitor with separate entrances.

Most

so-called Arab architecture is exemplified by asymmetrical placements of window

opening and decoration. The metaphor of ambulatories and public passages is a

history of surrender and intervention between neighbors and tribes as they

collected in cities like Babylon.

In the 1960s, Frei Otto designed the stadiums

for Munich Olympics using canvas and cables on a mammoth scale based on the

tent cable system developed by the Arabs. Much of this asymmetry is recalled in

both European and Turkish fortresses.

In the 1960s, Frei Otto designed the stadiums

for Munich Olympics using canvas and cables on a mammoth scale based on the

tent cable system developed by the Arabs. Much of this asymmetry is recalled in

both European and Turkish fortresses.

In the 1960s, Frei Otto designed the stadiums

for Munich Olympics using canvas and cables on a mammoth scale based on the

tent cable system developed by the Arabs. Much of this asymmetry is recalled in

both European and Turkish fortresses.

In the 1960s, Frei Otto designed the stadiums

for Munich Olympics using canvas and cables on a mammoth scale based on the

tent cable system developed by the Arabs. Much of this asymmetry is recalled in

both European and Turkish fortresses.

Africa’s

architectural technical legacy is its post and lintel construction where

horizontal, diagonal and vertical elements are attached at their intersecting

joints with hemp forming the outlines of what was later transferred down the

Nile (the northern section of the river flows almost entirely through desert,

from Sudan into Egypt) to Egypt to be the technological metaphor for Egyptian

palaces. These were transferred by the Sudanese to Egypt along with abundant

labor, wood and colorful pigment to decorate the buildings. These tied joints

were later reflected in the capitals and brackets of Greek architecture.

Medieval

architecture was dominated by palaces and castles surrounded by walls where the

court lived within and the serfs lived outside. The serfs’ houses were mud,

thatch and timber copies of the castles technology as poor subordinate -human

relations to those inside the wall. This metaphor was inherited from earliest

Egypt and lasted till their French Revolution (even to big New World cities

like New Amsterdam). The metaphoric-castle vocabulary of the times designed the

great halls, plates to eat off (since they were made of metal or“plate”), and

furniture which were not movable.

It is

the Renaissance where Europeans finally developed movables (moebles).The

medieval world had few movables aside from trunks which housed their belongings

as they had to be ready when raided to escape in an instant. So they sat on the

cases and soon these evolved into furniture with legs and arms, etc. All of

these had metaphoric decorations of animals and natural pallets and trees.

In

France during the so-called Gothic period, technologically the fly buttress and

use of the point rather than the vaulted arch revolutionize large spans and

building design. When considering building rather than tents the Indian,

Persian and Arabians also adopted this analogous pointed arch motif. For

politico-religious reasons (i.e. the Crusades) like the prohibition against the

sign of the cross, the Roman vaulted domes were also banned. The cathedral in

Chartres and Notre Dame in Paris exemplified this technology. Most famous was

the “flying buttress” used to transmit the horizontal force of a vaulted

ceiling through the walls and across an intervening space to a counterweight

outside the building. As a result, the buttress seemingly flies through the

air, and hence is known as a "flying" buttress. Thus the pointed arch

(the thrust of the supports crossed each other at the apex) and the long spans

within gave Gothic architecture its distinctive metaphoric image.

Renaissance

architecture was all based on the rediscovery of Roman ruins and the revival of

ancient literature which brought both an intellectual, political and artistic

rebirth to all of Europe. Starting in Florence and other Italian city states,

it later spread via France to the whole of Europe. Perspective drawing and

other artistic devices flourished including building, furniture and household

decorative items.

Metaphorical

new representations of the horizon, evidenced in the expanses of space opened

up in Renaissance painting, helped shape new humanist thought (Nuttgens,

Patrick (1983) and the way buildings were conceived and designed.

| Versailles:Baroque architecture |

Queen

Maria Theresa of Austria grasped both the implicit and explicit metaphor and

commissioned her palace to communicate its concern for the human scale and

employed hundreds of artisans to craft furniture, games, and decorations

designed to be metaphors of the color, shapes and forms of nature and

technology. Furthermore, and enamored with the finding of ruins in Italy she

had them transported and some rebuilt on Schönbrunn to connect her time with

the classical past. In fact Emperor Leopold hired Johann Bernard Fischer von

Erlach to produce a design in 1688. Maria Theresa could only be regarded as an

informed client (probably an opinionated one) and she got the “architect of the

court” Nicolo Pacassi to redesign the palace and the gardens. Schönbrunn is an

orchestration of metaphoric factors gathered by a variety of apparently

unrelated crafts and craftsman around them and subjects of the court’s

choosing. By so doing, these crafts were emulated by the court and citizens

exemplifying how human cognition is fundamentally shaped by various processes

of figuration (Gibbs, Jr., R. W (1993). This habitable metaphor was not meant

for the user to fully, continuously and forever recall all that went into its’

production. The palace and its grounds was one metaphor after the other

including the ruins, gardens and statues. Throughout the empire, in an

attempt to make the strange familiar (showing her gratitude to the Hungarians),

matching, copying and emulating the design of other buildings and adapting the

design of one to Schönbrunn adapted to the more familiar building in Vienna and

the surrounding villages.

| Schunbrunn |

| Petit Trianon |

|

| Chambord |

It was

no accident that when US cities began designing and building they copied the

European models of retail and commercial shops. Even the metaphors of extending

roof heights with false work to be taller than their neighbors were adapted and

still today is practiced in the international style of building design. The

Duomo in Milan is an important example of city-wide and public metaphor where

many artisans were employed to carve the many statues and gargoyles on its

facades. Each carving was a metaphor and the collection of them all

communicated the unity of passion and adherence to the church. This exemplified

the interaction view of metaphor where metaphors work by applying to the

principle (literal) subject of the metaphor to a system of “associated

implications” characteristic of the metaphorical secondary subject. These

implications were typically provided by the received “commonplaces” (general

beliefs or values that are widely shared within a culture) about the secondary

subject: “In this case the success of the metaphor rests on its success in

conveying to the reader some quieter defined respects of similarity or analogy

between the principle and secondary subject.”

Milan’s Duomo is only

one of hundreds of examples of this unified and diverse building metaphor (Boyd,

R (1993).

Remarkably,

the architectural beneficiary of free enterprise, democracy and the sovereignty

of the individual was the modern architecture which was metaphorically demarked

by the so-called Art Nouveau style. Art Nouveau (or Jugendstil – youth

art) which began in Paris and Munich was exemplified by its metaphorical signs

of leaves, vines and nature reminiscent of the tree-like forms of the Gothic

buttresses and arches. Art Nouveau encompasses a hierarchy of scales in design

architecture; interior design; decorative arts including jewelry, furniture,

textiles, household silver and other utensils, lighting and the full range of

visual arts. In some ways it was a precursor to the Bauhaus where modern

architecture really got its start, which eclipsed the Beaux Artes’ eclecticism.

The metaphors of contemporary and modern architecture were their abstract,

cubistic and plain design (lack of embellishments). They strove to be

impersonal, general and metaphorically dead. Not to belabor the

socio-political, design went on a competitive rampage between citizens, but

within the vernacular of the available materials, technology and design theory.

Bauhaus was also committed to achieve high quality design with machine-made

mass production. Modern architecture theory was applied to both public and

private enterprises producing public works and privately owned public

buildings. The use of structural iron and steel and steel reinforced concreted

changed the look, size and scale of building-types, especially the office

building which now, owing to the elevator, could convey people to great heights

to figuratively scrape the sky. Stadia, transportation terminal and

manufacturing buildings could be covered with long span steel beams, cables and

folded plates (some derived from origami). This exercised the “analogical

transfer theory” where instructive metaphors create an analogy between

a-to-be-learned- system (target domain) and a familiar system. (Mayer, R. E

(1993) Technically, not unlike classical Gothic, modern

architecture wanted to express the truth about the building’s systems,

materials, open lifestyles, use of light and air and bringing nature into the

building’s environment, not to mention ridding building of the irrelevant and

time-worn clichés of building design decoration, and traditional principles of

classical architecture as professed by the Beaux Artes movement. For equipoise

“unity, symmetry and balance” were replaced by “asymmetrical tensional

relationships” between, “dominant, subdominant and tertiary” forms; and, the

results of science and engineering influence on architectural design birthed a

new design metaphor. The Bauhaus found the metaphor in all the arts, the

commonalties in making jewelry, furniture, architecture, interior design,

decoration, lighting, and industrial design: even fine art, music and poetry.

They believed that there were principles of design that transferred from one to

the other techne.

|

| Bauhaus in Dessau Germany |

|

| Mies Van der Roh: Barcelona Pavilion |

However,

it was certainly affected by the instrumentalization industrialization of

architecture as argued under the maxim "form follows function"

(Banham, R. (1980). A disappointment to the purist was that the mainstays of

ancient metaphors were still alive and well including the commonplaces of turf,

identity, security, status, power, protection and shelter. In fact with the

unleashing of the global real estate boom, real estate investment trusts, and

free enterprise that the inordinate variety of metaphoric iconic building types

dwarfed anything of the past in such historically low-key places as Dubai,

Doha, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Jakarta, Manila, Tokyo, Las Vegas, Sydney, Hamburg,

Singapore, and Hawaii; not to mention the historically notorious places as New

York, Chicago, San Francisco, Paris, Berlin, etc.

Futurist

architecture was a metaphoric term alluding to the past compared with a

later period (Watkin, D. (2005). While it claimed to sever such ties and

present something new, in fact it talked about the future in terms of its

present. It was a metaphor which tried to make the strange (future) familiar by

talking about one time in terms of the other (Gordon, W. J. J. (1971).

“Futurist

architecture began as an early-20th century form of architecture characterized

by anti-historicism (where historicism is a theory that history is determined

by immutable laws and not by human agency) and long horizontal lines suggesting

speed, motion and urgency. Technology and even violence were among the themes

of the Futurists”. The epic film, “The Shape of Things to Come”, based on the

novel by H G Wells, was one of its important achievements. All of this was

eclipsed by contemporary science fiction movie making technologies and concepts

using artificial intelligence, time travel, supernatural and spiritual

manifestations.

Expressionist

architecture style was characterized by an early-modernist adoption of novel

materials, formal innovation, and very unusual massing; sometimes inspired by

natural biomorphic forms or sometimes by the new technical possibilities

offered by the mass production of brick, steel and especially glass. Morris

Lapidus’ Fountainbleu and Eden Roc Hotels are other such fine examples (Curtis,

W. J. R. (1987).

| Seagram Building by Phillip Johnson |

| Falling waters by Frank Lloyd Wright |

References

1

Akbar, Jamel A ;( 1988) Crisis in the Built

Environment: the Case of the Muslim City, Concept Media; distributed by. J.

Brill, Leiden; the Netherlands; formerly in Singapore, and moved to England.

1

Banham, Reyner; (1980) Theory and Design in the

First Machine Age, Architectural Press. (London)

2

Boyd, Richard; (1993) Metaphor and theory

change: What is” metaphor” a metaphor for? In Ortony, A (Ed), Metaphor and

thought, Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, United Kingdom

4)

4

Brown, Michael H ;( 1991) Mandala Symbolism:

(Reprinted from Coastal Pathways, Volume 3, No. 6, July, 1991, Virginia Beach,

Va.);

5

Ching, F. et.al. ;( 2006) A Global History of

Architecture, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ.

6

Curtis, William J. R. ;(1987) Modern

Architecture Since 1900, Phaidon Press, London

7

Fez-Barringten, Barie; (1993) Mosques and

Metaphors (Self-published),Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

8

Frampton, Kenneth; (1980) Modern Architecture, a

critical history. Thames & Hudson- Third Edition, (1992) ,London

9

Copplestone, Trewin; (1963) World architecture -

An illustrated history. Hamlyn, London.

10 Carrasco,

Pedro, and Paul Kirchhoff; (2008) The Oxford Encyclopedia of

Mesoamerican culture

(Instituto de Antropología (1963), Oxford, New York

1

Schmidt, Jurgem; “Baghdad Information”; Vol. 3;

(1964) Gebr. Mann; Berlin: available from

the German Archeological Institute :Baghdad Section; Athens, Greece

2

Fletcher, Banister; Cruickshank; (1976) Dan, Sir

Banister Fletcher's a History of Architecture, Architectural Press, 20th

edition. New York

3

Fuller, R. Buckminster; (1975, 1979) The whole

is more than the sum of its parts. Aristotle, Metaphysica; Max Wertheimer

Gestalt theory (1920s) and SYNERGETICS:

Explorations in the Geometry of Thinking by R. Buckminster Fuller in

collaboration with E. J. Applewhite; First Published by Macmillan Publishing

Co. Inc., New York

4

Gardiner, S.; (1974), “From Caves to Co-Ops”:

Evolution of the House, MacMillan Publishing Co., New York.

5

Gordon, William, J.J. ;( 1971) The metaphorical

Way of Knowing: Main currents in Modern Thought: and Synectics: Porpoise Books; Cambridge, Massachusetts.

6

Gibbs, Jr., Raymond W.; (1993) Process and

products in making sense of tropes; In .Ortony, A (Ed), Metaphor and thought,

Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, United Kingdom

7

Hugh, B. ;(1951) An introduction to English

medieval architecture, Faber and Faber, London

8

Hakim, Bassim: (1958) Culture and Built Form,

and Urban Design / Planning; Ara7. Hitchcock, Henry-Russell, the Pelican History

of Art: Architecture: Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries and bic-Islamic

Cities: building and planning principles; Penguin Books, New York.

9

Jeziorski, Michael; (1993) The shift from

metaphor to analogy in Western science, In .Ortony, A (Ed), Metaphor and

thought, Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, United Kingdom

10 Jencks,

Charles; (1993) Modern Movements in Architecture. Penguin Books Ltd - second

edition. In .Ortony, A (Ed), Metaphor and thought, Cambridge University Press;

Cambridge, United Kingdom

4)

4

Kuhn, Thomas S.; (1993) Metaphor in science;

Cambridge University Press. In .Ortony, A (Ed), Metaphor and thought, Cambridge

University Press; Cambridge, United Kingdom

5

Lakoff, George; (1993) The contemporary theory

of metaphor Cambridge University Press

In .Ortony, A (Ed), Metaphor and thought, Cambridge University Press;

Cambridge, United Kingdom

6

Mayer, Richard E.; (1993) The instructive

metaphor: Metaphoric aids to students’ understanding of science ; Cambridge

University Press and in Ortony, A (Ed),

Metaphor and thought, Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, United Kingdom

7

Miller, George A.; (1974) Images and models,

similes and metaphors MacMillan Publishing Co. New York

8

Nuttgens, Patrick;(1983) the Story of

Architecture, Prentice Hall, New Jersey

9

Sundell,

George; (2008) “Recovering Iraq’s

Past” initiative; The Oriental Institute of University of Chicago: The Diyala

Web site: http://oi.uchicago.edu/research/projects/diy/, Chicago

10 Pevsner,

Nikolaus; (1991) Pioneers of Modern Design: From William Morris to Walter

Gropius, Penguin Books Ltd., New York

11 Pylyshyn,

Zeon W.; (1993) Metaphorical imprecision and the “top down” research

strategy Cambridge University Press In .Ortony, A (Ed), Metaphor and thought,

Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, United Kingdom

12 Rumelhart,

David E. ;( 1991 & 1993) Some problems with the emotion of literal

meanings, Routledge, New York: (1991) and reprinted Journal of Pragmatics (1993)

13 Santayana. G. ;(1988) M.I.T. Press,

Cambridge, Massachusetts

14 Scully,

Vincent; (1988) American Architecture and Urbanism, Yale University, New

Haven

15 Strassler,

R. B.; (1942, repr. 1967, rev. ed. 2008) The Landmark Thucydides studies

by J. H. Finley: Thucydides, c.460–c.400 B.C., Greek historian of Athens

16 Watkin,

David; (2005), A History of Western

Architecture, Hali Publications, London

17 Weiss,

Paul; (1971) The Metaphorical Process: in Main Currents in Modern Thought:

Sept/Oct 1971; Vol28; Number 1, New Rochelle, New York

18 Wells,

H.G.; (1933) The shape of things to come, Hutchinson, UK (Now Random House)

19 Zarefsky,

David; (2005) Argumentation: A study of effective Reasoning, The Teaching

Company, Chantilly, Virginia

NOTE: all images shown in this monograph (as above and below) are not those of the author, but cut and pasted from the www, Internet. They are meant to illustrate the period but not necessarily any particular architect, building or place. Readers may find many such general and specific images on the www. Further, these illustrations do not appear in any of the author's commercially published work. No permissions have been attained from the source of the images and should not be reproduced or used without their permission.

Find partial credits for images below.

1. Temple of Augustus and Livia: //www.touropia.com/ancient-roman-temples/

2. Egyptian The Temple of Isis at Philae, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egyptian_temple

3.Fontainebleau Palace: http://www.musee-chateau-fontainebleau.fr/

4. Fort Knox: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Bullion_Depository

5.Vauban Fortress: Vauban Fortress://napoleonicscenarios.weebly.com/vauban-fortress.html

NOTE: all images shown in this monograph (as above and below) are not those of the author, but cut and pasted from the www, Internet. They are meant to illustrate the period but not necessarily any particular architect, building or place. Readers may find many such general and specific images on the www. Further, these illustrations do not appear in any of the author's commercially published work. No permissions have been attained from the source of the images and should not be reproduced or used without their permission.

Find partial credits for images below.

1. Temple of Augustus and Livia: //www.touropia.com/ancient-roman-temples/

2. Egyptian The Temple of Isis at Philae, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egyptian_temple

3.Fontainebleau Palace: http://www.musee-chateau-fontainebleau.fr/

4. Fort Knox: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Bullion_Depository

5.Vauban Fortress: Vauban Fortress://napoleonicscenarios.weebly.com/vauban-fortress.html

6. Governor's Palace in Williamsburg: http://www.history.org/almanack/places/hb/hbpal.cfm

7. Mandala:http://www.jyh.dk/indengl.htm#Mandala

8. Çatalhöyük Hose:Syria: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%87atalh%C3%B6y%C3%BCk

9. The Vitruvian Man Leonardo da Vinci:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vitruvian_Man

10. Empire:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Empire_style

11. Ziggurat: http://www.mesopotamia.co.uk/ziggurats/home_set.html

12. Gilgamesh statue: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gilgamesh

13. City of Sumer:http://www.strayreality.com/Lanis_Strayreality/sumerian_civilization.htm

14. The largest of the Pyramids at Giza is the "Great Pyramid": http://www.personal.psu.edu/mkw5102/giza.html

15. Mesoamerican architecture: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mesoamerican_architecture

16. Greek Architecture: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greek_architecture

17. Chinese Pagoda: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_pagoda

18. Frei Otto: Munich Olympics : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olympic_Stadium_(Munich)

19. Cathedral in Chartres: http://www.sacred-destinations.com/france/chartres-cathedral

20 Versailles:Baroque: http://architecture.about.com/od/periodsstyles/ig/Historic-Styles/Baroque.htm

21. Schunbrunn: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sch%C3%B6nbrunn_Palace

22. Chambord: Bloir: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ch%C3%A2teau_de_Chambord

23. Petit Trianon: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petit_Trianon

24. Bauhaus in Dessau Germany: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bauhaus

25. Seagram building: http://www.galinsky.com/buildings/seagram/

26. Falling waters by Frank Lloyd Wright: http://www.fallingwater.org/

Researched Publications: Refereed and Peer-reviewed

Journals: "monographs":

Barie Fez-Barringten; Associate

professor Global University

1. "Architecture the making of metaphors"

Main Currents in Modern Thought/Center for Integrative

Education; Sep.-Oct. 1971, Vol. 28 No.1, New Rochelle, New York.

2."Schools and metaphors"

Main Currents in Modern Thought/Center for Integrative

Education Sep.-Oct. 1971, Vol. 28 No.1, New Rochelle, New York.

3."User's metametaphoric phenomena of

architecture and Music":

“METU” (Middle East Technical University: Ankara,

Turkey): May 1995"

Journal of the Faculty of Architecture

4."Metametaphors and Mondrian:

Neo-plasticism and its' influences in architecture" 1993 Available on Academia.edu since 2008

5. "The Metametaphor of architectural education",

North Cypress, Turkish University. December, 1997

6."Mosques and metaphors" Unpublished,1993

7."The basis of the metaphor of Arabia" Unpublished, 1994

8."The conditions of Arabia in metaphor" Unpublished, 1994

9. "The metametaphor theorem"

Architectural

Scientific Journal, Vol. No. 8; 1994 Beirut Arab University.

10. "Arabia’s metaphoric images" Unpublished, 1995

11."The context of Arabia in metaphor" Unpublished, 1995

12. "A partial metaphoric vocabulary of Arabia"

“Architecture: University of Technology in Datutop;

February 1995 Finland

13."The Aesthetics of the Arab architectural

metaphor"

“International Journal for Housing Science and its applications”

Coral Gables, Florida.1993

14."Multi-dimensional metaphoric

thinking"

Open House, September 1997: Vol. 22; No. 3, United

Kingdom: Newcastle uponTyne

15."Teaching the techniques of making

architectural metaphors in the twenty-first century.” Journal of King Abdul Aziz University Engg...Sciences; Jeddah: Code:

BAR/223/0615:OCT.2.1421 H. 12TH

EDITION; VOL. I and

“Transactions” of

Cardiff

University, UK. April 2010

16. “Word Gram #9” Permafrost:

Vol.31 Summer 2009 University of Alaska Fairbanks; ISSN: 0740-7890; page 197

17. "Metaphors

and Architecture." ArchNet.org. October, 2009.at MIT

18. “Metaphor as an

inference from sign”; University of Syracuse

Journal of Enterprise

Architecture; November 2009: and nominated architect of the year in speical issue of Journal

of Enterprise Architecture explaining the unique relationship between

enterprise and classic building architecture.

19. “Framing the art

vs. architecture argument”; Brunel University (West London); BST: Vol. 9

no. 1: Body, Space & Technology Journal:

Perspectives Section

20. “Urban Passion”:

October 2010; Reconstruction & “Creation”;

June 2010; by C. Fez-Barringten;

http://reconstruction.eserver.org/;

21. “An architectural

history of metaphors”: AI & Society: (Journal of human-centered and

machine intelligence) Journal of Knowledge, Culture and Communication: Pub:

Springer; London; AI & Society located in University of Brighton, UK;

AI &

Society. ISSN (Print)

1435-5655 - ISSN (Online) 0951-5666 : Published

by Springer-Verlag;; 6 May 2010 http://www.springerlink.com/content/j2632623064r5ljk/

Paper copy: AIS Vol. 26.1. Feb. 2011; Online ISSN 1435-5655; Print ISSN

0951-5666;

DOI 10.1007/s00146-010-0280-8; : Volume 26, Issue 1 (2011), Page

103.

22. “Does

Architecture Create Metaphors?; G.Malek; Cambridge; August 8,2009

Pgs 3-12 (4/24/2010)

23. “Imagery or

Imagination”:the role of metaphor in architecture: Ami Ran (based on

Architecture:the making of metaphors); :and Illustration:”A Metaphor of

Passion”:Architecture oif Israel 82.AI;August 2010 pgs. 83-87.

24. “The sovereign built metaphor”: monograph converted to Power Point for presentation to

Southwest Florida Chapter of the American Institute of Architects. 2011

25.“Architecture:the

making of metaphors”:The Book;

Contract to publish: 2011

Cambridge

Scholars Publishing

12 Back Chapman Street

Newcastle upon Tyne

NE6 2XX

United Kingdom

12 Back Chapman Street

Newcastle upon Tyne

NE6 2XX

United Kingdom

Edited by

Edward Richard Hart,

0/2 249 Bearsden Road

Glasgow

G13 1DH

UK

Lecture:

ancient prehistoric, architecture, Architecture is a metaphor, art, metaphor, modern and contemporary architecture, traditional or classical art, Barie Fez-Barringten,